(A new article by the author on the top magazine Ancient Origins)

A century before Columbus, at the zenith of Venice’s splendour, two brothers, Nicolò and Antonio Zeno embarked an extraordinary journey to the far north following Viking trade routes on the shores of Canada. The travel log of the 14th-century Venetian brothers, which included the now famous Zeno map showing mysterious islands, and made reference to a mysterious benefactor Prince Zichmni, was discarded as a hoax, until recently new investigations. Who were these extraordinary men, what did they discover and why was their story subjected to damnatio memoriae since the 19th century?

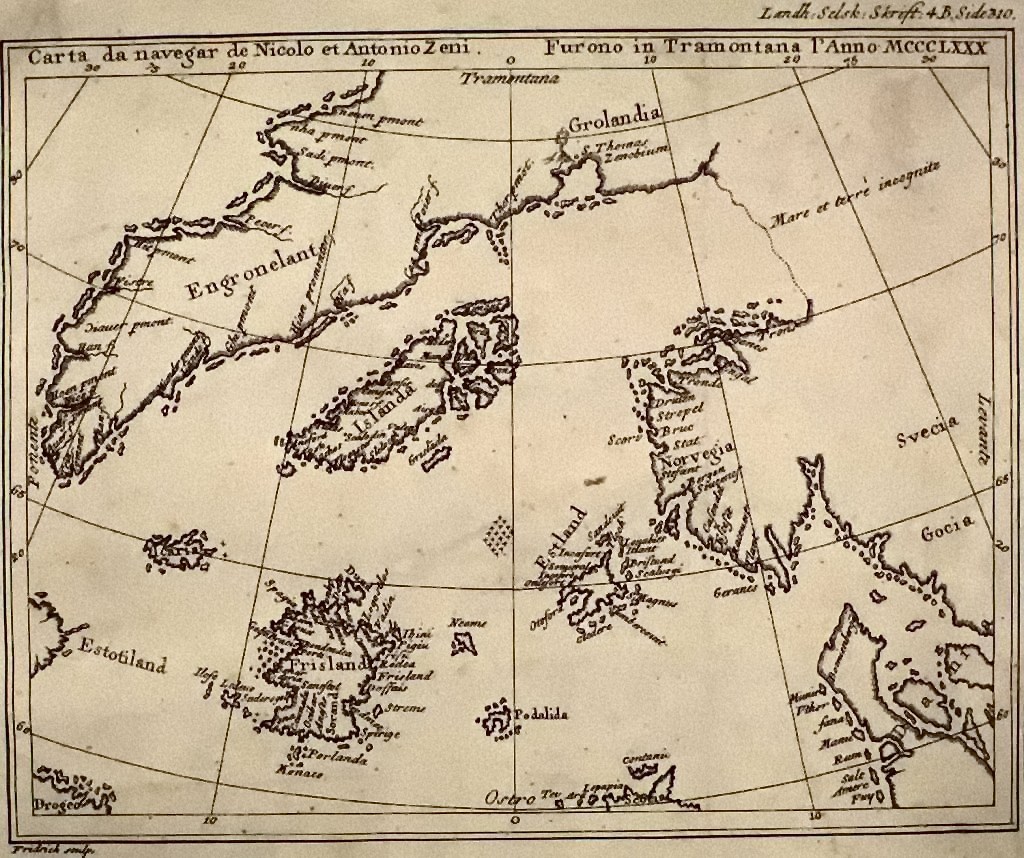

THE ZENO MAP

The Biblioteca Marciana in Venice, in St. Mark’s Square, holds a book dated to 1558, Dello Scoprimento dell’Isole Frislanda, Eslanda, Engroneland, Estotiland et Icaria fatto sotto il Polo Artico da due fratelli Zeni, (About the discovering of the islands of Frisland, Esland, Engroneland, Estotiland et Icaria made under the Arctic Pole by two Zeno brothers) published by Francesco Marcolini. In the introduction he explains that the narrative was written by Nicolò Zeno the Younger, great-nephew of Antonio and Nicolò Zeno, the two navigators whose travels are described in the text. Nicolò Zeno the Younger reports that he found five long letters of his ancestors in the family library and that he was able to proceed with a careful editing of their story, adding parts of the missing text on his own to connect the passages of the letters. With regret he adds that, having found them as a child in the family library and not comprehending their value he had irreparably ruined them so that a considerable part of the information was lost.

Venice had become the world capital of publishing in the 16th century and travel logs were always confirmed among the most successful books: Nicolò the Younger wanted to add prestige to his family name by publishing the exploits of his ancestors. He added a nautical map in the style of the time (carta da navegar) to the text, which came to be known in history as the Zeno Map.

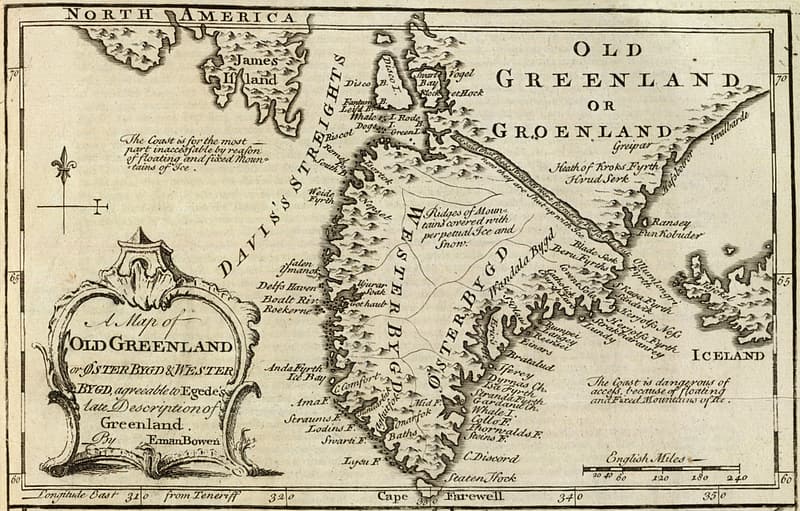

It is a typical map of the 14th-century which clearly distinguishes Norway, Sweden, Greenland and Iceland, as depicted by the respective place names on the map. But what differentiates this map are the mysterious islands that nobody had heard of at the time: Friesland, Icaria, Estotilanda, and even the coasts of the Newfoundland area in today’s Canada and parts of the southernmost areas. However, the map contained obvious positioning errors in latitude and longitude, so that some islands later found in reality were not at their designated geographical coordinates. Nonetheless, the book had some success and several editions began to spread, which came into the hands of Gerard Kremer, the great cartographer better known as Mercator, who was intrigued and used the Zeno Map for his Modern Map of the World (1569). Because of this the mysterious islands of the Zeno Map continued to be represented in nautical maps for some time.

THE ENIGMA OF FRISLANDA

Frisland continued to remain a mystery to navigators until 1787, when the French geographer Jean Nicolas Buache in his study “Mémoire sur l’isle de Frislande” observing the approximate latitude of the island suggested the possibility that it was the archipelago of the Faroe (or Feringian Islands).

Later the German geographer Henrich Peter von Eggers confirmed the hypothesis by comparing Marcolini’s text with the place names of the Faroe Islands, Munich for Munk, Sudero for Sutheroy, Nordero for Norðadalur, Andeford for Arnafjord, and others. The Viking colonization of the islands took place around the 9th century and the archipelago was called Faeroeisland, the island of sheep.

The conclusion reached by scholars is that Nicolò Zen, writing his letters, contracted the name, probably pronounced quickly, in medieval Venetian: Faroeisland/Friesland/Frieslanda. This thesis seems to be the most interesting and probable.

FAKE NEWS AND FAIRY TALES

However, Nicolò the Younger exacerbated the problem by drawing the archipelago of Frieslanda in the wrong position. It is also possible that the author used 1553 Matteo Prunes’ map in which an island called Fixlanda appears in a similar position. Precisely for this reason in 1835 the Danish admiral Christian Zahrtmann vehemently stated that the Zeno brothers’ voyages were a well-planned hoax, criticizing also other details of the story. It was only 40 years later that the Royal Geographical Society was able to prove the contrary. However, even today the travels of Antonio and Nicolò Zeno are still considered little more than a fairy tale by some, until recently.

Finally, the accurate investigation and travels of Andrea De Robilant, professor at the American University of Rome, who retraced the Zeno’s routes, unravelled the threads and completed the puzzle and awarded the Venetian navigators the place they deserve in history. His book (2011) Irresistible North: From Venice to Greenland on the Trail of the Zen Brothers combines historical and archival research with field visits, research in archives and enlists the help of local experts, concluding in fundamental results.

However, Nicolò the Younger contributed to the problem by drawing the archipelago of Frieslanda in the wrong position; it is also possible that the author used 1553 Matteo Prunes’ map in which an island called Fixlanda appears in a similar position.

Precisely for this reason in 1835 the Danish admiral Christian Zahrtmann vehemently stated that the Zen brothers’ voyages were a well-planned fake, criticizing also other details of the story, and only 40 years later the Royal Geographical Society was able to prove the contrary. However, even today the travels of Antonio and Nicolò Zen are still considered little more than a fairy tale.

The very accurate investigation and travels of Andrea De Robilant, professor at the American University of Rome, who retraced the Zeno’s routes, were necessary to put together a distorted and incomplete puzzle and to give Venetian navigators the place they deserve in history: his book Venetian Navigators: The Voyages of the Zen Brothers to the Far North is an excellence in this kind of studies because it combines historical and archival research with a field visit and investigations in archives and the help of local experts, which, as we will see, will give fundamental results.

But who were these men brave enough to reach the unknown lands of the Far North?

THE VENETIAN ZENO FAMILY

The Zeno family were among the most ancient, noble and famous families of Venice. According to some sources they arrived in the city state in the ninth century, contributing to the growth and power of the city throughout its history, always protagonists in politics, trade and defence of the lagoon.

Nicolò, Antonio and their brother Carlo, admiral and hero of the war against Genoa, lived during the Golden Age of the Venice Republic, when the Serenissima dominated the Adriatic, the Mediterranean, up to the Black Sea and beyond. It was an extraordinarily flourishing period, and the patronage of patrician families attracted the best artists of the time to their palaces.

The dynamic times fuelled an enthusiasm for explorative expeditions and the government of the Serenissima was perfectly aware of the need to expand its trade routes to other latitudes, following the always effective mercantile practice of diversifying investments. The Mediterranean and the Black Sea routes to Trebizond, the Crimea and the islands of Greece and Cyprus, were routes to be maintained at the price of wars. Continuous clashes with other naval powers such as the Ottoman Empire, hindered expansion to the east, but in Northern Europe, despite the power of the Hanseatic League, there was still room for Venice. By the 14th century she regularly sent her galleys in military convoys of seven to eight ships, beyond the Pillars of Hercules to open new trade routes.

THE JOURNEY OF NICOLO’ ZENO

In the winter of 1382-83 Nicolò Zeno – after a profitable and honoured career in commercial and military activities in the war against Genoa – at his own expense armed and fitted out his modest vessel with adequate armaments for defence at sea, and left for Flanders. The ship had previously been deployed in the Baltic Sea. Nicolò sailed without the protection of a convoy, a dangerous choice, but he was driven by the need to beat the competition and have maximum freedom of movement.

The Serenissima was at that time trying to reach Flanders by passing through the Tyrrhenian Sea and the Atlantic, to avoid the continuous dangers and onerous duties of the usual trade routes by land. An office in Bruges had already been established to manage flourishing trade contacts. Nicolò knew the so-called lingua franca, an idiom spoken in all ports, consisting of Greek, Venetian, Catalan, Latin, Arabic and other languages, which allowed merchants to communicate and conclude transactions. No written testimonies exist, but the language was functional, learned orally and with a simple grammar and reduced vocabulary, ultimately served the task very well. It was used during the Middle Ages and also in later periods, until the 19th century.

Nicolò’s voyage was complicated by storms since his entry into the English Channel and the ship was pushed first to the east and then to the north. The overcast sky prevented navigation by stars and not even the compass was helpful during such intense storms. According to the letters, the crew, pushed for days at extreme latitudes, landed on the island called Frislanda, unknown to the Venetians. Here they were attacked by the warlike natives and they would all have died if the Lord of the Islands, a mysterious prince called Zichmni, had not intervened and saved them, providing them food and shelter. The prince spoke Latin and in conversations with Nicolò, he explained that he was in Frislanda to quell the revolts of the natives. His kingdom included a vast area and archipelagos of islands.

Over the weeks, the prince observed the great seafaring skills of Nicolò and his sailors and proposed that they join him in his mission to subdue the islands. The Venetian accepted and after an appropriate period of time in the service of Prince Zichmni was named a knight by him.

THE MYSTERY OF PRINCE ZICHMNI

Among the many proposals of scholars to ascertain the true identity of Prince Zichmni, one of them seems the most plausible, despite the lack of official confirmation. The naturalist Johann Reinhold Forster in the 18th century proposed an interesting theory that links the mysterious Prince Zichmni to the House of Sinclair and in particular to Henry I Sinclair (or St. Clair, 1345-1400?), Count of Orkney and Lord of Rosslyn.

In fact, Sinclair was pronounced Zincler in the local vernacular and it is possible that an erroneous transcription of the name led to Zichmni. Moreover, in the period when Messer Nicolò arrived in Frislanda, Henry I was in the Faroe Islands to demand tributes from the warlike local populations on behalf of the Norwegian crown.

The biography of Henry I seems to fit perfectly into this historical puzzle. He was the son of William Sinclair, Lord of Rosslyn and the Norwegian noblewoman Isabella (Isobel), daughter of an Earl of Orkney. He served King Håkon of Norway in exchange for the title of Count of Orkney, which he obtained on August 2, 1379. His assignment included the reunification of Orkney, the Faroe Islands and Shetlands – which had rebelled against the king’s authority – to the Norwegian crown and the collection of taxes.

William Sinclair, Earl of Caithness, grandson of Henry I, became known as the builder of the Chapel of Rosslyn, made famous by the book The DaVinci Code.

ARRIVAL OF ANTONIO ZENO

Nicolò was an expert merchant and immediately understood the great opportunities that destiny had offered him. In 1383 he wrote to his brother Antonio, in Venice, about the extensive trade routes already established for centuries that brought fish and exchange goods from the islands to the mainland, Scotland, Flanders, Denmark, Norway, England. The letter arrived at Antonio the following year and in 1384 he left with a ship that he had bought and prepared for the long journey that would last many months, at least until the summer of 1385. However, he could not spend much time with his brother because Zichmni had dispatched Nicolò to a military expedition to Shetland, which was besieged by a cousin of the prince.

ISLAND OF ESTLANDA

According to the story a terrible storm decimated the prince’s ships, but they eventually managed to reach the Shetlands. Despite the coarse mistakes in reporting the islands on the map, the place names mentioned by Nicolò the Younger are easily identifiable in the name Estlanda (Shetlands) and the toponymy of the archipelago: Danberg (Danaberg), Bress (Bressay Island) which he erroneously placed near Iceland in Zeno’s Map, and others. In Estlanda the prince and Nicolò completed their mission and then proceeded to Iceland following the old Viking route. After Pythea of Massalia which landed there in the fourth century BC, Iceland was reached by Irish monks in the eighth century followed by Viking settlers in the following century. The latter settled in villages and the population grew to over 10,000 individuals by the 12th century. Norway conquered Iceland in 1264 imposing a forced trade but by the time Nicolò arrived, the bond with Norway had already weakened considerably.

ARRIVAL IN ICELAND

The letters of the Venetians provide details of extraordinary precision, for example they describe a monastery where volcanic geothermal power was used for heating, and running hot water was commonly used. The heat in the subsoil allowed the cultivation of vegetables and was used to bake bread without the aid of wood-burning ovens. The monks extracted the volcanic rocks from the mouth of the nearby volcano using them as building material. In his research work, Professor De Robilant tried to find this monastery among the seven active in Iceland in the 14th century. After the Reformation, which arrived here in 1531, the monasteries were destroyed and covered by volcanic ashes. Due to their decimation, the Zeno report was considered a fairy tale, but thanks to an archaeologist from Reykjavík, Professor De Robilant was able to identify the area where it was located and found local confirmation that even today bread is baked without ovens and vegetables are grown thanks to the heat of the subsoil.

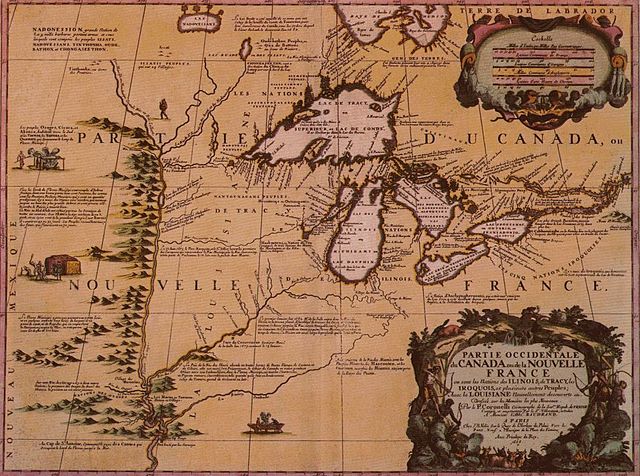

ESTOTILANDA AND CANADA

The narrative reports that later Messer Nicolò returned to Venice. A few references available in the archives speak of several political appointments but also of serious accusations of embezzlement that stained his name forever. These accusations also affected his brother Carlo, despite his fame and honor as a hero of the Serenissima. Instead, his brother Antonio decided to remain for another ten years in the service of Prince Zichmni as commander of the fleet and it is not clear whether he returned to Venice or not. In any case, it was during this period that the prince heard about some fishermen who had visited unknown lands called Estotilanda and Drogeo, and had remained there for decades only to return to their homeland, the Faroe Islands.

The prince invited Antonio to accompany him on an exploratory expedition that lasted several weeks. They could not reach their destination, but instead landed on another island, called Icaria, whose inhabitants proved hostile, preventing them from colonizing the area. They had no idea that they had arrived in another continent, in Newfoundland, north-eastern Canada. Estotilanda is to be identified in Nova Scotia. According to the fishermen in Estotilanda there would have been a Viking colony and this is certainly plausible. In Drogeo, the coastal area south of Newfoundland, one witness reported the existence of cannibals to whom he tried to teach the rudiments of fishing, but this statement could not be supported by any kind of evidence. Nicolò the Younger described the area using the expression “New World”. This phrase was not proper of a 14th century letter, but surely belonged to a man of the Renaissance as the author of the book. These interjections of the later author became the source of contention and casted doubt on the actual reality of some of the descriptions in the book.

Anyway, Prince Zichmni and Antonio Zeno had actually arrived near the coasts of North America and even if they could not disembark, the journey continued. The explorers were pushed by the strong wind to the north, reaching the southern tip of Greenland on June 2, 1398. They called this area ‘Promontory of the Trinity’ (today Cape Farvel). Finding a mild and submissive Eskimo population, Prince Zichmni made it a new colony and began the systematic exploration of the long coastal area by building the first settlements, while Antonio decided to return to the Faroe Islands with some sailors. Finally, Prince Zichmni returned to the Faroe Islands to die on an uncertain date, probably in 1404, in battle.

COLONIZING GREENLAND

The kingdom of Norway in the 14th century also included Greenland and for two centuries they used consolidated Viking routes that went back and forth between these two lands, stopping in the islands. There is also clear evidence of Viking settlements in North America, more precisely Nova Scotia and Newfoundland. As far as Greenland is concerned, there are letters between Bishop Erik Gnupsson of Greenland and Pope Pasquale II (as early as 1124 a bishop had been appointed in Gardar, in the extreme south of Greenland with a suitable bishopric), in which the issue of interbreeding marriages in the colonies of North America was discussed. The bishop had visited these colonies and ascertained the existence of the problem by writing to the Pope.

Later, climatic change, known today as the Little Ice Age, made the normal continuation of life in the colonies impossible and they practically ceased to exist. A similar condition also faced Iceland, between volcanic eruptions and wars. Then about a century later, things slowly began to return to normal and travel and trade between the islands and the continent resumed.

FOLIE OF NICOLO’ THE YOUNGER

The text by Nicolò the Younger presents several inaccuracies: first of all in the attached map the location of the islands are incorrect. Where he recounts about the monastery and the use of the thermal and geothermal springs in Greenland, it is quite evident that it was Iceland. Probably these errors derive from the fact that he no longer had the complete letters to base his facts, but only some parts. However, De Robilant states that he was able to precisely determine the location of the monastery near the Icelandic volcano Myrdal.

There are also inaccuracies regarding the date of departure of Nicolò Zeno which does not seem to be 1380, but rather the winter of 1382/83. Moreover, contrary to what the author of the book states, Nicolò Zeno did not die during a trip to Northern Europe, but returned to Venice where the city archives record his political and commercial activity for many years.

FACT OR FICTION

What can be inferred from Nicolò the Younger’s text? Firstly the letters from which he drew the information, describes detailed geographical and local areas confirming the truthfulness of the writing as only those who knew the lands in the North very well and had visited the villages and monasteries in Iceland and Greenland could provide such details. It is ultimately an eyewitness account.

Moreover, Nicolò and Zichmni reached the coasts of Newfoundland a century before Columbus by discovering, or rather rediscovering, the American coasts, already reached by the Vikings in the 10th century.

The author of the book, Nicolò the Younger, member of the Council of Ten, hero of the Serenissima and hydraulic engineer, was a man of great value, esteemed and respected in Venice, and of well-known morality, who held extremely important positions in political and military life, certainly not an imaginative author. The travels of Nicolò and Antonio Zeno were oral tradition in Venice, familiar to other traveling merchants, children and grandchildren of colleagues of the Zeno. The Zeno family was historically embedded in Venetian life. Nicolò the Younger had no need to write a partly invented story or to add romantic details as he was a pragmatic and a military man who wrote for the nobles and merchants of his time.

The theory describing Prince Zichmni as Henry I Sinclair finds new and interesting confirmations. Thanks to the documented field research work of Professor Andrea De Robilant, the Map of Zeno and the travel narrative of the brothers Zeno can be accepted in large part as historical evidence, limited by certain inaccuracies, but still confirming the characters of the two navigators, Nicolò and Antonio Zeno.

Pierluigi Tombetti is a historian, author and writer who has thoroughly investigated the ideological and social reasons and motivations of National Socialism. Author, writer, columnist and editor in the historical and archaeological field, he is the author of reportages, articles and essays/novels including SYNCHRONICITY – Flight 9941

REFERENCES

Da Mosto A. 1933.I navigatori Niccolò e Antonio Zeno. Gli Archivi di Stato italiani. Miscellanea di Studi storici, vol. I, Firenze

De Robilant A. 2011. Irresistible North: From Venice to Greenland on the Trail of the Zen Brothers. Alfred A Knopf.

Forster J. R. 1786. History of the Voyages and Discoveries Made in the North. London.

Gambino Longo S. 2012 .Alter Orbiset exotisme boréal: le grand Nord selon les Humanistes Italiens. Camenae 14 .

Horodowich E. 2014. Venetians in America: Nicolò Zen and the Virtual Explo-ration of the New World. Renaissance Quarterly, 67.

Lucas F.W. 1898. The Annals of the Voyages of the Brothers Nicolo and Antonio Zeno in the North Atlantic about the end of the fourteenth century, and the claim founded thereon to a Venetian discovery of the America: a criticism and an indictment, London

Padoan, G. 1998. Gli Ulissidi dell’Atlantico. Veneti nel mondo, Novembre

Smith B. 1974. Prince Henry Sinclair: His Expedition to the New World in 1398. New York

Russo L 2013. L’America dimenticata. I rapporti tra le civiltà e un errore di Tolomeo. Milano 2013.

Zarthmann C. 1835. Remarks on the Voyages to the Northern Hemisphere Ascribed to the Zenis of Venice. The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society, 5 (1835)

Zeno N. 1558. Dei Commentarii del viaggio in Persia di M. Caterino Zeno. Venezia